As I mentioned at our meeting today, there'll be a short reading tomorrow afternoon (June 9th) at 5:00 PM in McMicken 255 featuring students published in the winter and spring issues of Short Vine, UC's undergrad literary journal. You can pick up copies of the new spring print issue tomorrow at the reading tomorrow and check out the winter issue online at http://shortvinejournal.com.

Don't forget that Short Vine will be reading submissions again in the fall for our next online issue. Be sure to send some of the great work you produced this term in for the students to look at! You can follow Short Vine on Facebook through this page.

Wednesday, June 8, 2011

Monday, May 23, 2011

Writing Prompt #10: The Lipogram

A lipogrammatic text is one that's contrained by the omission of one (or a group of) letters. Perhaps it's easier to demonstrate the possibilities of the form by giving you a few examples:

- Georges Perec's 1969 novel, La Disparation (translated as A Void) runs for approximately 300 pages without using the letter E (the most common letter in French). Gilbert Adair pulled off an amazing feat by translating the original as A Void in 1995, remaining faithful not only to the storyline, but also its linguistic restriction. Perec wrote several additional texts in this fashion, including the shorter novella, Les Revenentes (translated by Ian Monk as The Exeter Text: Jewels, Secrets, Sex).

- Walter Abish's 1974 novel, Alphabetical Africa, contains 52 chapters, the first of which only contains words beginning with the letter A, the second, words beginning with A and B, and so on until, in chapter 26 any and all words are permissible. Abish then starts taking letters away again, starting with Z, until the final chapter which, once again, consists solely of words starting with A.

- Christian Bök's 2001 book (its genre is ambiguous) Eunoia, which consists of five chapters, each named for one of the vowels and comprised solely of words containing that respective vowel. In addition, Bök has instituted several other rules, including making use of at least 98% of all existing words featuring the given vowel, as well as specific tasks, including writing about the act of writing, a feast, a debauch, a nautical journey, etc.

The purpose of such writing exercises is two-fold: first to provide restrictions that might ultimately yield worthwhile work, and second to force the writer to avoid common words and phrases and/or discover atypical language to suit their expressive purposes. For your final prompt, I'd like you to write a poem that's restricted in some lipogrammatic fashion but I'll leave the specifics up to you: you can chose to avoid a certain letter or group of letters (one possibility: choose a brief word and avoid all those letters), to use only one vowel or to narrow your restrictions to words beginning with certain letters; you can also shift your restriction from stanza to stanza (or section to section) as you see fit. Be sure to note what restriction you set for yourself when you post your poem.

Friday, May 20, 2011

Submit to Short Vine!

Here's the message regarding Short Vine submissions. If you get them in today (even after the 5:00 deadline), that'll be fine.

If you've submitted poetry or fiction to any of the English department's annual writing contests, your work is already under consideration for publication in Short Vine, but we wanted to provide an opportunity for students who missed that deadline to send their work our way.

Please send up to three poems or one short story (up to 25 pages in length) to shortvine2011@gmail.com along with a brief bio, no later than 5:00 PM this Friday. Work should be sent as attachments in Word or Rich Text Format, with your name and title in the filename. Please indicate in the subject line whether your submission is poetry or fiction.

All UC undergraduates are welcome to submit work to Short Vine regardless of their major. Those students who were published in our online winter issue are welcome to submit to our spring print issue as well.

We look forward to seeing your work!

- the Short Vine editorial team [http://shortvinejournal.com/]

Please send up to three poems or one short story (up to 25 pages in length) to shortvine2011@gmail.com along with a brief bio, no later than 5:00 PM this Friday. Work should be sent as attachments in Word or Rich Text Format, with your name and title in the filename. Please indicate in the subject line whether your submission is poetry or fiction.

All UC undergraduates are welcome to submit work to Short Vine regardless of their major. Those students who were published in our online winter issue are welcome to submit to our spring print issue as well.

We look forward to seeing your work!

- the Short Vine editorial team [http://shortvinejournal.com/]

Monday, May 16, 2011

Writing Prompt #9: The Sum of Its Parts

We've talked about this several times over the course of the term, but since it came up again in Friday's class, I thought it might be worth making a prompt out of the idea of fragmentation and linking.

At the heart of this technique is the notion that what we're trying to say in a poem doesn't have to be accomplished in one continuous train of thought. Much like the way in which line and stanza breaks can create a necessary pause or add emphasis, breaking your poem into discreet sections can give you the room to make dramatic shifts in perspective or characterization or let a particularly resonant idea ring out in your readers minds. This technique is most effective when the connection between the fragments isn't explicitly clear (leaving it to your reader to bridge those gaps) or if you choose to work around a topic in an abstract fashion, considering different facets of the idea at hand with each section.

One well-known poem written in this form is Wallace Stevens' "Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird":

Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird

IAmong twenty snowy mountains,The only moving thingWas the eye of the blackbird.

III was of three minds,Like a treeIn which there are three blackbirds.

IIIThe blackbird whirled in the autumn winds.It was a small part of the pantomime.

IVA man and a womanAre one.A man and a woman and a blackbirdAre one.

VI do not know which to prefer,The beauty of inflectionsOr the beauty of innuendoes,The blackbird whistlingOr just after.

VIIcicles filled the long windowWith barbaric glass.The shadow of the blackbirdCrossed it, to and fro.The moodTraced in the shadowAn indecipherable cause.

VIIO thin men of Haddam,Why do you imagine golden birds?Do you not see how the blackbirdWalks around the feetOf the women about you?

VIIII know noble accentsAnd lucid, inescapable rhythms;But I know, too,That the blackbird is involvedIn what I know.

IXWhen the blackbird flew out of sight,It marked the edgeOf one of many circles.

XAt the sight of blackbirdsFlying in a green light,Even the bawds of euphonyWould cry out sharply.

XIHe rode over ConnecticutIn a glass coach.Once, a fear pierced him,In that he mistookThe shadow of his equipageFor blackbirds.

XIIThe river is moving.The blackbird must be flying.

XIIIIt was evening all afternoon.It was snowingAnd it was going to snow.The blackbird satIn the cedar-limbs.

While Stevens' poem doesn't necessarily add up to a clear and definitive picture he does approach his topic from many unique angles. A more contemporary master of this style is Rae Armantrout, who works in a minimalist style, frequently combining seemingly disconnected segments to create a wide-ranging poetic picture. Here's her poem, "The Subject":

The Subject

It’s as if we’ve just been turned humanin order to learnthat the beetle we’ve caughtand are now devouringis our elder brotherand that weare a young prince.

*

I was just going to clickon “Phoebe is changedinto a mermaidtomorrow!” when suddenlyit all changedinto the imageof a Citizen watch.

*

If each moment is in lovewith its imagein the mirror ofadjacent moments

(as if matter stuttered),

then, of course, we’re restless!

“What is a surface?”we ask,

trying to change the subject.

While this technique works well in a more abstract fashion, it can also quite successfully be used in a narrative fashion, with each section serving as a micro-chapter of sorts. Two great examples of this are Allen Ginsberg's "After Lalon" and Richard Brautigan's "The Galilee Hitchhiker."

Armed with these examples, I'd like you to try to write a poem that works in a similar fashion, using fragmentation and linking to great poetic effect.

Monday, May 9, 2011

Writing Prompt #8: The O'Hara-esque Walk Poem

The late Frank O'Hara, a key member of the New York School's first generation, had an all-too-brief poetic career — he was tragically killed in a freak accident in 1966 — and yet he left behind a prodigious body of work, largely because he successfully integrated his writing habits into his daily life, creating a characteristic style. Here's the poet's tongue-in-cheek back cover blurb to one of his best known collections, Lunch Poems:

Often this poet, strolling through the noisy splintered glare of a Manhattan noon, has paused at a sample Olivetti to type up thirty or forty lines of ruminations, or pondering more deeply has withdrawn to a darkened ware- or firehouse to limn his computed misunderstandings of the eternal questions of life, coexistence, and depth, while never forgetting to eat lunch, his favorite meal.

O'Hara's peripatetic style is often shorthanded as "I do this, I do that," and one of his best known poems in this style is "The Day Lady Died," written upon hearing news of the passing of jazz singer Billie Holiday, also known as Lady Day:

The Day Lady Died

It is 12:20 in New York a Friday

three days after Bastille day, yes

it is 1959 and I go get a shoeshine

because I will get off the 4:19 in Easthampton

at 7:15 and then go straight to dinner

and I don’t know the people who will feed me

I walk up the muggy street beginning to sun

and have a hamburger and a malted and buy

an ugly NEW WORLD WRITING to see what the poets

in Ghana are doing these days

I go on to the bank

and Miss Stillwagon (first name Linda I once heard)

doesn’t even look up my balance for once in her life

and in the GOLDEN GRIFFIN I get a little Verlaine

for Patsy with drawings by Bonnard although I do

think of Hesiod, trans. Richmond Lattimore or

Brendan Behan’s new play or Le Balcon or Les Nègres

of Genet, but I don’t, I stick with Verlaine

after practically going to sleep with quandariness

and for Mike I just stroll into the PARK LANE

Liquor Store and ask for a bottle of Strega and

then I go back where I came from to 6th Avenue

and the tobacconist in the Ziegfeld Theatre and

casually ask for a carton of Gauloises and a carton

of Picayunes, and a NEW YORK POST with her face on it

and I am sweating a lot by now and thinking of

leaning on the john door in the 5 SPOT

while she whispered a song along the keyboard

to Mal Waldron and everyone and I stopped breathing

A few other favorites written in this style are "A Step Away From Them" and "Personal Poem," and you can see traces of this style in the work of Ted Berrigan, particularly in poems like "Today in Ann Arbor" and (in a very compact form) "10 Things I Do Every Day":

10 Things I Do Every Day

wake up

smoke pot

see the cat

love my wife

think of Frank

smoke pot

see the cat

love my wife

think of Frank

eat lunch

make noises

sing songs

go out

dig the streets

make noises

sing songs

go out

dig the streets

go home for dinner

read the Post

make pee-pee

two kids

grin

read the Post

make pee-pee

two kids

grin

read books

see my friends

get pissed-off

have a Pepsi

disappear

see my friends

get pissed-off

have a Pepsi

disappear

Part of the beauty of this style is its all-inclusiveness — this form admits all occurrences and emotions, and it's list-like order is set up beautifully for experiments with flow, pacing, repetition, etc. The everyday events of your life can have great poetic resonance and the people who surround you can be just as interesting in their humanness as grand heroic figures. The trick, in part, is finding the aesthetic in the mundane, and letting your ear (and eye) guide you through your world, finding the interesting elements, the names, sounds, sights and bits of speech that will make your poem feel both true to your life but also engaging to your reader.

So for this week, I'd like you to play around a little with this form, finding poetry in your daily routines. Use the O'Hara and Berrigan poems as inspirations, but feel free to adapt the form however you see fit to match your own needs.

Friday, May 6, 2011

Your Final Portfolios

As mentioned at the start of the term, you'll be expected to hand in a final portfolio at the end of the term. This will include the following things:

- Revisions of 5-6 poems that you wrote this term (either poems that were workshopped formally or poems that you wrote in response to our various prompts), including both the original and revised versions along with a brief explanation (a few sentences for each) of what changes you made, how workshop comments affected your alterations, etc.

- Two (2) copies of your finished chapbook (for me), plus a copy for everyone else in the workshop (so 20 copies altogether). *

- A final evaluation of your experience in our workshop (details below).

* However, I encourage you to make a larger set (say 40-50 copies) so you can distribute them to friends and family. While printing/photocopying costs will increase in this case, you won't really be spending more in terms of paper, cover stock, etc. as you'll be buying a lot more than you'll use, even if you split with a few classmates.

For your final evaluation, I'd like you to answer the following questions, with your overall essay running to about 2.5-3 pages in length:

- In what ways have your poetics — or the way in which you think about poetry, it's meaning, its usefulness, etc. — changed over the course of this workshop? How would you describe your poetics now?

- Have your compositional habits changed at all due to this workshop, and if so, how? What prompt(s) did you find most useful and which one(s) could you just not get into?

- Did this workshop live up to your expectations (or, perhaps, exceed them)? What would you say were the most useful things that you'll take away from this experience?

Also, it goes without saying that you should be caught up with any and all workshop evaluations of your classmates, and should have posted responses to at least 8 of the 10 workshop prompts I've posted throughout the quarter.

I haven't yet decided whether we'll gather for one last class meeting during our allotted exam period or whether we'll have our last meeting on the final Friday of the quarter. I'm leaning towards exam week as a) it'll give you more time to finish everything, and b) we'll have more than 50 minutes to discuss your work. If we go with the exam week meeting, it will be from 12:00-2:00 on Wednesday, June 8th.

Some Useful Information For Your Chapbooks

In addition to thinking about the poems you'll select for your final portfolio and chapbook, you should already be giving some thought to the design and binding for your chapbook. Hopefully the time we spend today going through a wide array of possible constructions, sizes, shapes and bindings will be useful, and to help you as you more actively start planning, here are a few how-tos that might be of use:

- A primer on Japanese book-sewing techniques, taken from the Boy Scouts' magazine Boy's Life

- WikiBooks' tutorial on Zine Making has a tremendous amount of worthwhile information in regards to binding possibilities, layout, etc.

- Poets and Writers tutorial on how to make a saddle-stitched chapbook

Aside from the content of your book, you'll want to think about things like your cover materials, art and layout. The easiest and cheapest option is to buy what's called cover stock (here's an example from Staples; Office Depot has some different options for colors) — it's a sturdy card stock that comes in a variety of colors, from pastels and neutrals to brights, and that will pass through either a photocopier or a printer without difficulty. You might want to simply print in black on your covers, or use a combination of stamps, cut-outs glued to the cover, or embossing to create your design. A variety images will print well over this sort of stock, from simpler line drawings to photographs, or you can go with a purely textual design. An interesting compromise might be to make a design that uses only text, but manipulated in an abstract way. Ron Silliman's latest book, The Alphabet, has a cover by Geof Huth that's constructed out of letters (see at right, you'll recall seeing this image as part of this week's concrete poetry prompt). Once your card stock comes out of the printer or copier it will likely have warped a little from the heat of the condenser, so stack them (waiting until they've dried if the ink hasn't set) and then put a few heavy books over them so they'll flatten out again. Another option that a number of students pursued last quarter was using wallpaper as cover stock, then gluing a small title card onto the front cover.

You might also wish to use endpapers — a single sheet of paper, often colored, patterned or textured — that goes between the cover and the interior pages. Again, browsing the aisles of your local office supply warehouse will give you some ideas for possibilities: you might wish to use a complementary color (the last book I made, for example, had bright red endpapers to liven up the ash-grey covers), or you can use vellum (tracing paper), some sort of patterned writing paper, or hell, cut sheets to fit out of the newspaper. I've always done layout for covers in PowerPoint (my favorite free and ubiquitous image compositor), which allows you to easily resize images, match them in terms of size, create and manipulate text boxes, etc. When putting your covers together, don't forget that the front will be the righthand side, the back the left.

For interior layout, here are a few recommendations. First, you can accomplish a lot in Microsoft Word, setting the page layout as landscape and then creating two columns. You have built-in rulers to measure distance from edges and widths of text, which is helpful. Be sure to leave enough breathing room around the edges of of the page, as well as on the left margin of the righthand column (for the last project I put together, I left a half-inch at both the top and the bottom, set the right margin and the space between columns at an inch each, and left a half-inch as the far-right margin). You'll want to decide upon a standard format for your chapbook: What font will you use? What size (I recommend using a 10 or 11 pt., no larger)? What size will you make your titles (you can make them the same size or increase by 2pts. of the body text)? Will you underline them? Will you center them or make them flush left? How many lines will you skip before your title, and how many between your title and the start of the poem? Finally, after you've decided on your list of poems, I wholeheartedly making two different page layouts — start by posting the title page, blank pages and poems in the order you want them to appear, simply going from column to column, and getting an idea of when and where a poem will go over to a second page, if there will be issues with margins, etc. Then save this document once under some name, and resave under a second name. Keep both documents open at the same time, and start shifting around the material so that it'll be in the order you'll want to print in. If all else fails and this becomes way too frustrating for you, it's fine to either construct a chapbook that doesn't require folding or to just print on one side of the page (technically, this is called the "recto," i.e. the righthand page; the lefthand page is the "verso").

Before printing sufficient numbers of covers and book guts to make your print run, I recommend printing just one copy and assembling it, so that you can troubleshoot problematic layouts, issues with fonts, margins, etc. Once you've made any necessary changes, then go ahead and print. When I've done these sorts of projects in the past, I've used a laserwriter printer (usually at the office I was working in) to print the covers, and have used a photocopier with duplexing capabilities to produce the necessary number of sets of book guts (note: if you opt to photocopy, never use the photo settings — I know that it seems like it will produce a higher-quality image, but it will make your text fuzzy). One final decision you'll need to make is what paper to use. In the past, I've used thicker, higher-quality paper with a high cotton content (what's called thesis or resume paper), and this not only gives the book more heft, but also makes your pages less transparent. A box of this sort of paper can run you $30-40 however, so a few of you might want to chip in and split one, or just use regular copy paper. Think of the math this way: if you're making a 16-page book, then you're going to need 4 sheets per book, and say you're making 40 books, then that's 160 pages altogether. A ream has 500 sheets, so three of you can split a box of thesis paper, have 20 sheets leftover for screwups or damaged pages, and pay about $10 each. Or if you're making 40 24-page books (6 sheets) two of you can split a ream for $15 each.

Also, don't forget that you can literally cut your costs in half by making smaller chapbooks (two to a sheet/set of paper) and then cutting them in half with a guillotine, however this isn't for the faint of heart, and you run the risk of ruining huge amounts of your printed components with imprecise cutting. I don't recommend the guillotine for the faint of heart. And though copying and/or printing costs something there are ways around it — hit up a parent or sibling who has access to a copier or laserwriter at work, or shop around to find a cheaper option. The print shop in the basement of McMicken is relatively cheap, only a few cents a page.

In general, I recommend splitting costs if at all possible, whether that's buying a sampler of cover stock and divvying up the individual colors, splitting paper, sharing a needle and a spool of thread, or going in on a stapler together. It's also not a terrible idea to team up in terms of production. You might not believe it, but once all of your printing is done, you can put together 40 or 50 books in half an hour while watching television, but you can invite a few classmate over, and knock out all of your books in an hour then celebrate with the non-alcoholic beverage of your choice.

We can talk about the ins and outs of book production in our free time over the next few classes, and I'm more than happy to answer any questions you might have via e-mail or during my office hours as well.

Additionally, here are some supplies you might want to consider purchasing, depending on how you want to lay out your chapbooks:

You might also wish to use endpapers — a single sheet of paper, often colored, patterned or textured — that goes between the cover and the interior pages. Again, browsing the aisles of your local office supply warehouse will give you some ideas for possibilities: you might wish to use a complementary color (the last book I made, for example, had bright red endpapers to liven up the ash-grey covers), or you can use vellum (tracing paper), some sort of patterned writing paper, or hell, cut sheets to fit out of the newspaper. I've always done layout for covers in PowerPoint (my favorite free and ubiquitous image compositor), which allows you to easily resize images, match them in terms of size, create and manipulate text boxes, etc. When putting your covers together, don't forget that the front will be the righthand side, the back the left.

For interior layout, here are a few recommendations. First, you can accomplish a lot in Microsoft Word, setting the page layout as landscape and then creating two columns. You have built-in rulers to measure distance from edges and widths of text, which is helpful. Be sure to leave enough breathing room around the edges of of the page, as well as on the left margin of the righthand column (for the last project I put together, I left a half-inch at both the top and the bottom, set the right margin and the space between columns at an inch each, and left a half-inch as the far-right margin). You'll want to decide upon a standard format for your chapbook: What font will you use? What size (I recommend using a 10 or 11 pt., no larger)? What size will you make your titles (you can make them the same size or increase by 2pts. of the body text)? Will you underline them? Will you center them or make them flush left? How many lines will you skip before your title, and how many between your title and the start of the poem? Finally, after you've decided on your list of poems, I wholeheartedly making two different page layouts — start by posting the title page, blank pages and poems in the order you want them to appear, simply going from column to column, and getting an idea of when and where a poem will go over to a second page, if there will be issues with margins, etc. Then save this document once under some name, and resave under a second name. Keep both documents open at the same time, and start shifting around the material so that it'll be in the order you'll want to print in. If all else fails and this becomes way too frustrating for you, it's fine to either construct a chapbook that doesn't require folding or to just print on one side of the page (technically, this is called the "recto," i.e. the righthand page; the lefthand page is the "verso").

Before printing sufficient numbers of covers and book guts to make your print run, I recommend printing just one copy and assembling it, so that you can troubleshoot problematic layouts, issues with fonts, margins, etc. Once you've made any necessary changes, then go ahead and print. When I've done these sorts of projects in the past, I've used a laserwriter printer (usually at the office I was working in) to print the covers, and have used a photocopier with duplexing capabilities to produce the necessary number of sets of book guts (note: if you opt to photocopy, never use the photo settings — I know that it seems like it will produce a higher-quality image, but it will make your text fuzzy). One final decision you'll need to make is what paper to use. In the past, I've used thicker, higher-quality paper with a high cotton content (what's called thesis or resume paper), and this not only gives the book more heft, but also makes your pages less transparent. A box of this sort of paper can run you $30-40 however, so a few of you might want to chip in and split one, or just use regular copy paper. Think of the math this way: if you're making a 16-page book, then you're going to need 4 sheets per book, and say you're making 40 books, then that's 160 pages altogether. A ream has 500 sheets, so three of you can split a box of thesis paper, have 20 sheets leftover for screwups or damaged pages, and pay about $10 each. Or if you're making 40 24-page books (6 sheets) two of you can split a ream for $15 each.

Also, don't forget that you can literally cut your costs in half by making smaller chapbooks (two to a sheet/set of paper) and then cutting them in half with a guillotine, however this isn't for the faint of heart, and you run the risk of ruining huge amounts of your printed components with imprecise cutting. I don't recommend the guillotine for the faint of heart. And though copying and/or printing costs something there are ways around it — hit up a parent or sibling who has access to a copier or laserwriter at work, or shop around to find a cheaper option. The print shop in the basement of McMicken is relatively cheap, only a few cents a page.

In general, I recommend splitting costs if at all possible, whether that's buying a sampler of cover stock and divvying up the individual colors, splitting paper, sharing a needle and a spool of thread, or going in on a stapler together. It's also not a terrible idea to team up in terms of production. You might not believe it, but once all of your printing is done, you can put together 40 or 50 books in half an hour while watching television, but you can invite a few classmate over, and knock out all of your books in an hour then celebrate with the non-alcoholic beverage of your choice.

We can talk about the ins and outs of book production in our free time over the next few classes, and I'm more than happy to answer any questions you might have via e-mail or during my office hours as well.

Additionally, here are some supplies you might want to consider purchasing, depending on how you want to lay out your chapbooks:

Saddle/Booklet Staplers: I've looked around the web and haven't been able to find a small hand-held booklet stapler like the one I showed you in class, but here are a few relatively inexpensive options if you'd like to invest in one:

- Sparco Stapler (only 1 left) - $11

- Sparco Long-Reach Stapler (appears to be the same as above but $4 more) - $15

- Stanley Anti-Jam Long-Reach Stapler - $23

- Swingline Long-Reach Stapler - $29

- Stanley Anti-Jam Booklet Stapler - $36

Of course, there are a number of ways you can design/bind your chapbooks that won't require a saddle stapler (including using a size smaller than 8.5 x 6.5 [i.e. standard copy paper folded in half], stapling through the edge of the cover, sewing, using elastic thread in a loop, etc.), but if you want to minimize some other complications, you'll likely need a long-reach or saddle stapler. You might also want to purchase some sort of bone folder or guitar slide, to help you make a hard crease easily and without the risk of papercuts. Here are some options on Amazon:

Wednesday, May 4, 2011

Workshop Schedule: Round 3

Friday, May 6: chapbook overview

Monday, May 9

Chris Todd (lead reviewer: Morgan A.)

Samantha E. (lead reviewer: Chris W.)

Wednesday, May 11

Anabel Morales (lead reviewer: Lucas B.)

Brandy H. (lead reviewer: Jenny O.)

Friday, May 13

Emily S. (lead reviewer: Francis P.)

Taylor L. (lead reviewer: Claire H.)

Monday, May 16

Johnneca J. (lead reviewer: John Z)

Chelsea W. (lead reviewer: Elyse)

Wednesday, May 18

Elyse T. (lead reviewer: Chelsea)

Claire H. (lead reviewer: Johnneca J.)

Friday, May 20

Francis P. (lead reviewer: Chris T.)

Morgan A. (lead reviewer: Samantha W.)

Monday, May 23

Jenny O. (lead reviewer: Ashley C.)

Chris W. (lead reviewer: Taylor L.)

Wednesday, May 25

Lucas B. (lead reviewer: Jamie F.)

John Z. (lead reviewer: Emily S.)

Friday, May 27

Samantha W. (lead reviewer: Anabel Morales)

Ashley C. (lead reviewer: Brandy H.)

Monday, May 30: No Class — Memorial Day

Wednesday, June 1:

Jamie F. (lead reviewer: Samantha E.)

Friday, June 3: final wrap-up

Monday, May 9

Chris Todd (lead reviewer: Morgan A.)

Samantha E. (lead reviewer: Chris W.)

Wednesday, May 11

Anabel Morales (lead reviewer: Lucas B.)

Brandy H. (lead reviewer: Jenny O.)

Friday, May 13

Emily S. (lead reviewer: Francis P.)

Taylor L. (lead reviewer: Claire H.)

Monday, May 16

Johnneca J. (lead reviewer: John Z)

Chelsea W. (lead reviewer: Elyse)

Wednesday, May 18

Elyse T. (lead reviewer: Chelsea)

Claire H. (lead reviewer: Johnneca J.)

Friday, May 20

Francis P. (lead reviewer: Chris T.)

Morgan A. (lead reviewer: Samantha W.)

Monday, May 23

Jenny O. (lead reviewer: Ashley C.)

Chris W. (lead reviewer: Taylor L.)

Wednesday, May 25

Lucas B. (lead reviewer: Jamie F.)

John Z. (lead reviewer: Emily S.)

Friday, May 27

Samantha W. (lead reviewer: Anabel Morales)

Ashley C. (lead reviewer: Brandy H.)

Monday, May 30: No Class — Memorial Day

Wednesday, June 1:

Jamie F. (lead reviewer: Samantha E.)

Friday, June 3: final wrap-up

Writing Prompt #7: Into the Archives

This is less of a prompt and more of a useful reminder, and not necessarily an exercise that will produce something this week (though I'd encourage you to come up with something before the quarter is over). Whether you've been writing for a few months or a few years, you probably have some unused material lying around in your archives: maybe just a great title that you've never used, a few scattered lines or even almost-ready pieces that were abandoned for some reason and never picked up again.

So what I'd like to encourage you to do is take a look at those computer files, those e-mails, those old notebooks, and see what you can do with it. I'm a big fan of cooking competitions like Chopped (watch below) where the contestants are given unexpected raw materials and expected to come up with something great in a flash, and that's sorta what you'll be doing here.

We leave old projects behind for a number of reasons — including the fact that they're just not good — but I've often been happily surprised to go back to a forgotten document and find something that I like a lot, and have even found fully-formed poems that I'm very happy with. While it's rare to find a complete poem, it's very likely that you'll find a few good lines, or a good image, something you can work with, whether that means using it as as starting point for new writing or combining them with similar materials from other abandoned poems to make a new/old poem.

This winter I was invited to submit a poem for a collection on the topic of alchemy, and wound up coming up with a new piece that drew together lines from old computer files and old notebooks from over the past 17 years — whiny notebook mewlings from high school, college poems, essays from my working years, grad school stories, etc., which was combined with new material to make something that attempted to approximate my entire writing life. You can do the same thing, even if your writing life has only been a few months!

This is a particularly good exercise when your writerly esteem needs a bit of a boost or the words just aren't flowing, or as an exercise unto itself. I'll make a thread on Blackboard where folks can post any poems that they come up with through this method.

Monday, May 2, 2011

Writing Prompt #6: Concrete and Visual Poetry

This week's prompt is a little out of the ordinary, yet part of a long tradition within poetry: concrete or visual poetry.

To spur your interest, here are a few concrete pieces that work in a number of different ways:

Regardless of what approach you take, you should have fun with this assignment! Trial and error will be key here — you're not going to get it right the first time, but if you play around a little bit with the forms you're likely to come up with something wonderful. Also, you're very likely going to need to upload an image file (preferably a jpg) to the thread, rather than a Word doc, so try to make sure that the file's not too huge. If you don't already know how to do so, learning how to take a screenshot on your respective computer platform will likely be useful.

For this assignment, I want you to get your hands dirty interacting with text on the rawest, most basic level. You're not necessarily going to be writing a poem in the traditional sense (as you'll see from the examples below) — instead you'll be using letters, numbers and punctuation marks to create some sort of image, symbol or pattern. To do this, you might want to work within your traditional word processing mode, but subvert that process by doing things like overlaying text boxes, playing around with the spacing between letters (which you can access through the font menu in Word) or using different fonts. You might instead decide to make your piece using an image editor, or in a more tactile way with a typewriter, stencils, or even by drawing it.

To spur your interest, here are a few concrete pieces that work in a number of different ways:

| |

| Geof Huth, "EEEeeG" |

|

| Geof Huth, "Construction of the Alphabet" |

.jpg) |

| Geof Huth, START (21 September 2010) |

Geof Huth is a well-established contemporary concrete poet, whose work has greatly inspired younger generations of authors, such as Paul Siegell, whose "book trailer" for *wild life rifle fire* you can watch below:

A classic example of the concrete poetry form is Guillaume Apollinaire's "Calliagrammes," first published in 1918:

|

| Guillaume Apollinaire, Il Pleut (It's Raining) |

While Huth's work is more of a self-conscious subversion of typographic and symbolic conventions, Apollinaire's concrete poems are actual full-fledged poems, which just happen to take different shapes. Here, for example, is an English translation of one of them:

A third option is to work with text in a way that's more textural or patternish, as we see in the examples below:

| Charles Bernstein, from Veils |

|

| Emiter Franczak, Poezja Konkretna |

Aside from these typographic approaches to texture/pattern, you could go with a hand-scripted design. These Brion Gysin visual poems, for example, are asemic (i.e. they don't actually say/mean anything) but are inspired by Arabic script:

Regardless of what approach you take, you should have fun with this assignment! Trial and error will be key here — you're not going to get it right the first time, but if you play around a little bit with the forms you're likely to come up with something wonderful. Also, you're very likely going to need to upload an image file (preferably a jpg) to the thread, rather than a Word doc, so try to make sure that the file's not too huge. If you don't already know how to do so, learning how to take a screenshot on your respective computer platform will likely be useful.

Monday, April 25, 2011

Writing Prompt #5: PoemWeek

Don't forget that we won't be meeting this Wednesday and Friday, as I'll be out of town fulfilling a number of professional obligations. As promised, here's a writing prompt that will last you the entire week. This assignment will play with your faculties for remembering and forgetting — both will be important facets of the overall process.

You'll start today with a poem — this can either be a new one or one you've written previously, and for your own sake shouldn't be too long. Write down a brief description of the poem (perhaps 2-3 sentences long): its emotions, its action, its setting, its development, its abstract concepts, etc.

Every day for the rest of the week, you'll attempt to reconstruct the original poem from memory — if necessary, you may consult the description you've written, but you can't refer to the poem itself or the new drafts that you'll write each day. Keep going until the week is up. Then once the final version has been written, take a look at your other drafts and make comparisons: what elements were preserved throughout and which changed? This is where the length is key, because your poem shouldn't be so short that you can memorize it off the bat and then simply repeat that every day, and yet it shouldn't be so long that you'll have trouble remembering the basic elements. To create a final version to post to Blackboard, you'll want to bring together all of the novel elements of those variant drafts into one version, and you might want to write a little note to go with the poem talking about how the work was altered. Feel free to make use of repetition (if you get different interesting versions of lines and/or sections) or to work with large-scale variation if there are very significant differences among your drafts.

Much like last week's prompt, this assignment is intended to help you more effectively write around a given topic or idea, generating a larger, more complex body of raw materials, ideas, actions, images from which you can draw as you craft subsequent drafts. The revision process will be even more important here as you recompose your poem from memory, working through problems with organization or phrasing and/or finding new ways to proceed.

A short-term version of this prompt is to attempt to recreate a poem from memory — any poem, from one of your own to work by your favorite poet to something workshopped in class today. For this assignment, however, I'd like you to do the full-scale seven (or five) day version.

Monday, April 18, 2011

Writing Prompt #4: A Set Lexicon

One main way in which poetry differs from prose is the importance of every last word, phrase and even punctuation mark. We want our language to be as vivid and imaginative as possible, and at the same time to have a pleasing sonic interplay with the words surrounding it, however this isn't always easy to achieve on the first pass. Likewise, throughout the first round of our workshop we've stressed the importance of specificity, of concreteness, as a way to make our work seem more real, more visual, more appealing to our readers. Taken together, this is quite a tall order — how exactly are you supposed to do all of these things at once? Well, one way to start is to think intently about language.

So today's prompt — inspired in part by our having recently seen several workshop poems that exemplified and/or needed attention to this technique — will ask you to cast a wide net for poetic to gather the raw materials of language you'll need for your poem. Because I'm going to ask you to explore the intricacies of the language subset pertaining to one idea, one thing, one place, etc., I'm calling this exercise "A Set Lexicon." For this prompt, an object poem might be your best bet, though you could also do a landscape/scene, or work around an abstract emotion — there are lots of possibilities, so find the one that works best for your needs.

As a hypothetical example, consider the word "apple." What sorts of ideas come to mind when you hear that word? Perhaps color, so you might start by thinking "red, green, yellow" and then hit a wall. So you shift gears again — "sweet, tart, juicy" — now aside from taste, what other senses can you bring into play? "Waxy, crunch, bite, firm, shiny." What visuals might you get? "An apple orchard, a worm in an apple, an apple on the teacher's desk, the apple waiting in your lunch bag." What phrases come to mind? "The apple of my eye. An apple a day keeps the doctor away. The Big Apple." What about cultural associations? "Eve and the forbidden apple. William Tell shooting the apple off of his son's head." What specific words or names do you think of? "Mackintosh, Fuji, Braeburn, Granny Smith, Winesap" Keep going until you run out of ideas, writing everything you come up with down. Now go back and look over your list: here you have some really wonderfully vivid raw materials with which you can construct a poem, so do so!

|

| Robert Pinsky, former U.S. Poet Laureate |

One of the best examples of this sort of technique in action is Robert Pinsky's classic poem "Shirt." Here, we see him take a simple concept, the shirt, and take it in a number of strange associative directions. Some of my favorite parts of the poem, however, are devoid of narrative — instead they're the places where Pinsky weaves clever music out of the specific parts of the shirt, all of the special, arcane language that applies to it.

Now, you might not necessarily write a ton of poems in this fashion, but what it's priming you to do is activate that list mode when you find yourself stuck for a specific word that'll serve as a hook for your readers, or when you're revising a poem and seeking to clear up any vague language.

Monday, April 11, 2011

Workshop Schedule: Round 2

Friday, April 15

Emily Schwieterman (lead reviewer: Francis Pospisil)

Samantha Ewing (lead reviewer: Emily Schwieterman)

Johnneca Johnson (lead reviewer: Anabel Morales)

Monday, April 18

Chris Wiggins (lead reviewer: Claire Hayden)

Chris Todd (lead reviewer: Brandy Huber)

Elyse Terrell (lead reviewer: Taylor La Rocca)

Wednesday, April 20

Brandy Huber (lead reviewer: Samantha Ewing)

Taylor La Rocca (lead reviewer: John Zajac)

Anabel Morales (lead reviewer: Morgan Anderson)

Friday, April 22

Claire Hayden (lead reviewer: Elyse Terrell)

Lucas Bezerra (lead reviewer: Johnneca Johnson)

Francis Pospisil (lead reviewer: Chris Todd)

Monday, April 25

Samantha Wilson (lead reviewer: Ashley Cagle)

Ashley Cagle (lead reviewer: Chris Wiggins)

Morgan Anderson (lead reviewer: Samantha Wilson)

Wednesday, April 27: No Class — Professor Conference

Friday, April 29: No Class — Professor Conference

Monday, May 2

Jamie Fox (lead reviewer: Jenny Otto)

Jenny Otto (lead reviewer: Lucas Bezerra)

Chelsea White (lead reviewer: Jamie Fox)

Wednesday, May 4

John Zajac (lead reviewer: Chelsea White)

Emily Schwieterman (lead reviewer: Francis Pospisil)

Samantha Ewing (lead reviewer: Emily Schwieterman)

Johnneca Johnson (lead reviewer: Anabel Morales)

Monday, April 18

Chris Wiggins (lead reviewer: Claire Hayden)

Chris Todd (lead reviewer: Brandy Huber)

Elyse Terrell (lead reviewer: Taylor La Rocca)

Wednesday, April 20

Brandy Huber (lead reviewer: Samantha Ewing)

Taylor La Rocca (lead reviewer: John Zajac)

Anabel Morales (lead reviewer: Morgan Anderson)

Friday, April 22

Claire Hayden (lead reviewer: Elyse Terrell)

Lucas Bezerra (lead reviewer: Johnneca Johnson)

Francis Pospisil (lead reviewer: Chris Todd)

Monday, April 25

Samantha Wilson (lead reviewer: Ashley Cagle)

Ashley Cagle (lead reviewer: Chris Wiggins)

Morgan Anderson (lead reviewer: Samantha Wilson)

Wednesday, April 27: No Class — Professor Conference

Friday, April 29: No Class — Professor Conference

Monday, May 2

Jamie Fox (lead reviewer: Jenny Otto)

Jenny Otto (lead reviewer: Lucas Bezerra)

Chelsea White (lead reviewer: Jamie Fox)

Wednesday, May 4

John Zajac (lead reviewer: Chelsea White)

Writing Prompt #3: Joe Brainard Remembers. Do You?

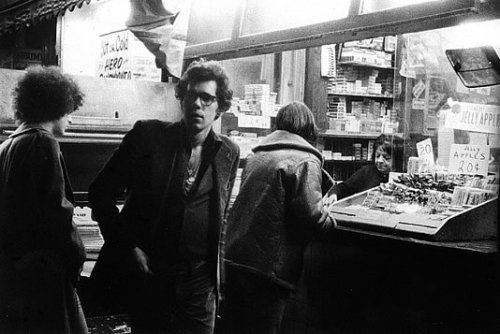

The late, great Joe Brainard (shown here outside of New York poets' oasis Gem Spa) was well-known as both an artist and writer, though far more prolific as the former than the latter. While much of his literary focus was directed towards covers and illustrations for books by his New York School friends (including Ted Berrigan, Ron Padgett, Anne Waldman, Frank O'Hara and John Ashbery) he did leave behind one modest yet indelible masterpiece: I Remember. First published in three small volumes from the independent press Angel Hair — I Remember (1970), I Remember More (1972) and More I Remember More (1973) — that were brought together in its present form in 1975. I Remember has continued to captivate audiences in the intervening decades, with Paul Auster praising it as "one of the few totally original books I have ever read," and both Georges Perec and Gilbert Adair creating book-length interpretations of their own.

The power of I Remember lies in its simplicity and imitability. Consisting of hundreds of short prose passages, each consisting of a single memory and beginning with the words "I remember," Brainard's book calls out for us to mimic his form, documenting our own lived experiences in a similar fashion. Here are some selections from the book, cut and pasted from web sources:

While these excerpts aren't all contiguous (they're pasted from three different places) you can get a sense of how certain themes and ideas carry over from one remembrance to another, and also how one memory can spur another, whether directly or obliquely. Also, while all of these memories relate to Brainard's childhood, there are great many in the book that are more contemporaneous, dating from a few weeks or a few years ago vs. a few decades ago.

So for this assignment, I'd like you to stoke the fires of your memory and see what comes out. Don't feel any restrictions in regards to length — you can be as long or as short as you'd like.

The power of I Remember lies in its simplicity and imitability. Consisting of hundreds of short prose passages, each consisting of a single memory and beginning with the words "I remember," Brainard's book calls out for us to mimic his form, documenting our own lived experiences in a similar fashion. Here are some selections from the book, cut and pasted from web sources:

I remember when, in high school, if you wore green and yellow on Thursday it meant that you were queer.

I remember when, in high school, I used to stuff a sock in my underwear.

I remember that for my fifth birthday all I wanted was an off-one-shoulder black satin evening gown. I got it. And I wore it to my birthday party.

I remember my first sexual experience in a subway. Some guy (I was afraid to look at him) got a hard-on and was rubbing it back and forth against my art. I got very excited and when my stop came I hurried out and home where I tried to do an oil painting using my dick as a brush.

I remember my parents’ bridge teacher. She was very fat and very butch (cropped hair) and she was a chain smoker. She prided herself on the fact that she didn’t have to carry matches around. She lit each new cigarette from the old one. She lived in a little house behind a restaurant and lived to be very old.

I remember the first time I got a letter that said “After Five Days Return To” on the envelope, and I thought that after I had kept the letter for five days I was supposed to return it to the sender.

I remember the kick I used to get going through my parents’ drawers looking for rubbers. (Peacock.)

I remember when polio was the worst thing in the world.

I remember pink dress shirts. And bola ties.

I remember when a kid told me that those sour clover-like leaves we used to eat (with little yellow flowers) tasted so sour because dogs peed on them. I remember that didn’t stop me from eating them.

I remember the first drawing I remember doing. It was of a bride with a very long train.

I remember my first cigarette. It was a Kent. Up on a hill. In Tulsa, Oklahoma. With Ron Padgett.

I remember my first erections. I thought I had some terrible disease or something.

I remember the only time I ever saw my mother cry. I was eating apricot pie.

I remember when my father would say "Keep your hands out from under the covers" as he said goodnight. But he said it in a nice way.

I remember when I thought that if you did anything bad, policemen would put you in jail.

I remember Dorothy Collins.

I remember Dorothy Collins’ teeth.

I remember planning to tear page 48 out of every book I read from the Boston Public Library, but soon losing interest.

I remember my grade school art teacher, Mrs Chick, who got so mad at a boy one day she dumped a bucket of water over his head.

I remember Moley, the local freak and notorious queer. He had a very little head that grew out of his body like a mole. No one knew him, but everyone knew who he was. He was always ‘around’.

I remember liver.

I remember when hoody boys wore their blue jeans so low that the principal had to put a limit on that too. I believe it was three inches below the navel.

I remember one football player who wore very light faded blue jeans, and the way he filled them.

I remember when my father would say ‘Keep your hands out from under the covers’ as he said good night. But he said it in a nice way.

I remember the chair I used to put my boogers behind.

I remember ‘queers can’t whistle’.

I remember how many other magazines I had to buy in order to buy one physique magazine.

I remember a girl in school one day who, just out of the blue, went into a long spiel all about how difficult it was to wash her brother’s pants because he didn’t wear underwear.

I remember a pinkish-red rubber douche that appeared in the bathroom every now and then, and not knowing what it was, but somehow knowing enough not to ask.

I remember a little boy who said it was more fun to pee together than alone, and so we did, and so it was.

I remember ‘dress up time’ (Running around pulling up girl’s dresses yelling ‘dress up time’).

I remember a fat man who sold insurance. One hot summer day we went to visit him and he was wearing shorts and when he sat down one of his balls hung out.

I remember that it was hard to look at it and hard not to look at it too.

I remember a very early memory of an older girl in a candy store. The man asked her what she wanted and she picked out several things and then he asked her for her money and she said. ‘Oh, I don’t have any money. You just asked me what I wanted, and I told you.’ This impressed me to no end.

While these excerpts aren't all contiguous (they're pasted from three different places) you can get a sense of how certain themes and ideas carry over from one remembrance to another, and also how one memory can spur another, whether directly or obliquely. Also, while all of these memories relate to Brainard's childhood, there are great many in the book that are more contemporaneous, dating from a few weeks or a few years ago vs. a few decades ago.

So for this assignment, I'd like you to stoke the fires of your memory and see what comes out. Don't feel any restrictions in regards to length — you can be as long or as short as you'd like.

Thursday, April 7, 2011

Keeping on Pace

A quick heads-up regarding the speed of posting poems: please remember that your poems should be posted three (3) days prior to your workshop so that your classmates will have plenty of time to respond to them. We all have busy schedules and while we want to give honest effort in responding to the workshop poems, we can't do so if they're posted right before the class itself. Looking at the boards, for example, I see that only one of tomorrow's poems is posted. I've created threads for next week's workshops as well, so please post your poems as early as possible.

Additionally, I'm quite impressed to see that the majority of you have kept on pace with workshop responses (looking at the number of thread participants, it seems like all but a few people have posted comments on each poem). So I won't have to do what I did last term — namely, spending a full two hours going through, thread by thread, and logging who did and didn't respond — I'm going to start tallying responses week by week. This weekend, I'll go through the first week's workshops, and I'll continue a week at a time throughout the term, so if you haven't yet posted responses to those poems, please do so as soon as possible.

As I said on our first day, a workshop is a social contract — a symbiotic agreement that your peers will give the same serious attention to your work that you give to theirs — and most of you seem to be getting this perfectly. Failure to respond to your colleagues' work in a timely fashion is one of the biggest ways in which your grades might be negatively impacted at the end of the term, and rather than get buried in late responses in weeks 9 & 10, you can save yourself a lot of trouble by making up any missing work now.

Additionally, I'm quite impressed to see that the majority of you have kept on pace with workshop responses (looking at the number of thread participants, it seems like all but a few people have posted comments on each poem). So I won't have to do what I did last term — namely, spending a full two hours going through, thread by thread, and logging who did and didn't respond — I'm going to start tallying responses week by week. This weekend, I'll go through the first week's workshops, and I'll continue a week at a time throughout the term, so if you haven't yet posted responses to those poems, please do so as soon as possible.

As I said on our first day, a workshop is a social contract — a symbiotic agreement that your peers will give the same serious attention to your work that you give to theirs — and most of you seem to be getting this perfectly. Failure to respond to your colleagues' work in a timely fashion is one of the biggest ways in which your grades might be negatively impacted at the end of the term, and rather than get buried in late responses in weeks 9 & 10, you can save yourself a lot of trouble by making up any missing work now.

Monday, April 4, 2011

Writing Prompt #2: Voices of the Other, Voices of the Inanimate

|

| "Je est un autre" ("I is another") — Arthur Rimbaud |

Poetry is often seen as a non-fictional genre, even as an autobiographical genre, and though the perspective we often write from — especially when we use the pronoun "I" — is our own, that doesn't necessarily need to be the case. When reading others' poetry, it's important to remember that the voice isn't necessarily issuing from the poet herself, and conversely, this is a useful reminder that we need not always be bound by our own point of view when writing.

A persona poem is one written from a fictional perspective, not unlike an actor getting into a role. It might take the form of a short vignette (like both of William Blake's poems titled "The Chimney Sweeper") or a longer character study (like Randall Jarrell's "The Woman at the Washington Zoo," or Frank Bidart's epic "Herbert White," a favorite poem of James Franco, who made a short film based on the poem). A persona poem might also be written from the perspective of an animal (like Gregory Corso's "The Mad Yak" or Philip Levine's "Animals Are Passing From Our Lives"), or could be written from a fictional perspective about a real person (or a preexisting character from a novel, film, myth, etc.), implementing a technique that's called "historiographic metafiction" (or "metapoetry," in this case).

You might even go so far as to write a poem from the point of view of an inanimate object (like Richard Brautigan's "The Sawmill" or Howard Moss' "Einstein's Bathrobe"), though in this case you'd still want to suffuse it with as much character, as much voice, emotion, perspective, etc. as you'd give to a fictional character you'd created.

So here are many different options for writing a work that comes from a voice other than your own. For this week's assignment, you might want to just write one poem of any sort, or try both a persona poem and a poem from the perspective of a non-living object, or maybe two persona poems written almost in dialogue with one another (two sides of the same story, perhaps). Regardless of the approach you take, make sure your response is posted by the end of the week.

A persona poem is one written from a fictional perspective, not unlike an actor getting into a role. It might take the form of a short vignette (like both of William Blake's poems titled "The Chimney Sweeper") or a longer character study (like Randall Jarrell's "The Woman at the Washington Zoo," or Frank Bidart's epic "Herbert White," a favorite poem of James Franco, who made a short film based on the poem). A persona poem might also be written from the perspective of an animal (like Gregory Corso's "The Mad Yak" or Philip Levine's "Animals Are Passing From Our Lives"), or could be written from a fictional perspective about a real person (or a preexisting character from a novel, film, myth, etc.), implementing a technique that's called "historiographic metafiction" (or "metapoetry," in this case).

You might even go so far as to write a poem from the point of view of an inanimate object (like Richard Brautigan's "The Sawmill" or Howard Moss' "Einstein's Bathrobe"), though in this case you'd still want to suffuse it with as much character, as much voice, emotion, perspective, etc. as you'd give to a fictional character you'd created.

So here are many different options for writing a work that comes from a voice other than your own. For this week's assignment, you might want to just write one poem of any sort, or try both a persona poem and a poem from the perspective of a non-living object, or maybe two persona poems written almost in dialogue with one another (two sides of the same story, perhaps). Regardless of the approach you take, make sure your response is posted by the end of the week.

Friday, April 1, 2011

The Rest of Workshop Round One

Here's the workshop schedule for the remainder of our first round. As we discussed in class today, instead of trying to pack in four rounds this quarter, we'll keep this more ambitious pace of three 12-minute workshops a day until the first round is over, then slow down for the last two rounds with two longer workshops a day. We'll set up the schedule for round two as we get close to the end of this one.

I've also created threads for all of next week's workshops. Please remember that you should post your poems three days before the workshop date (or as close to then as possible) so that your peers will have plenty of time to respond to your work.

Monday, April 4:

Chris Wiggins (lead reviewer: Samantha Ewing)

Francis Pospisil (lead reviewer: Claire Hayden)

Anabel Morales (lead reviewer: Chelsea White)

Wednesday, April 6:

Claire Hayden (lead reviewer: Morgan Anderson)

Jamie Fox (lead reviewer: Johnneca Johnson)

Taylor La Rocca (lead reviewer: Anabel Morales)

Friday, April 8:

Lucas Bezerra (lead reviewer: Brandy Huber)

Johnneca Johnson (lead reviewer: John Zajac)

Samantha Ewing (lead reviewer: Taylor La Rocca)

Monday, April 11:

Ashley Cagle (lead reviewer: Chris Wiggins)

John Zajac (lead reviewer: Francis Pospisil)

Brandy Huber (lead reviewer: Ashley Cagle)

Wednesday, April 13:

Jenny Otto (lead reviewer: Samantha Wilson)

Samantha Wilson (lead reviewer: Chris Todd)

Chris Todd (lead reviewer: Jenny Otto)

I've also created threads for all of next week's workshops. Please remember that you should post your poems three days before the workshop date (or as close to then as possible) so that your peers will have plenty of time to respond to your work.

Monday, April 4:

Chris Wiggins (lead reviewer: Samantha Ewing)

Francis Pospisil (lead reviewer: Claire Hayden)

Anabel Morales (lead reviewer: Chelsea White)

Wednesday, April 6:

Claire Hayden (lead reviewer: Morgan Anderson)

Jamie Fox (lead reviewer: Johnneca Johnson)

Taylor La Rocca (lead reviewer: Anabel Morales)

Friday, April 8:

Lucas Bezerra (lead reviewer: Brandy Huber)

Johnneca Johnson (lead reviewer: John Zajac)

Samantha Ewing (lead reviewer: Taylor La Rocca)

Monday, April 11:

Ashley Cagle (lead reviewer: Chris Wiggins)

John Zajac (lead reviewer: Francis Pospisil)

Brandy Huber (lead reviewer: Ashley Cagle)

Wednesday, April 13:

Jenny Otto (lead reviewer: Samantha Wilson)

Samantha Wilson (lead reviewer: Chris Todd)

Chris Todd (lead reviewer: Jenny Otto)

Sunday, March 27, 2011

Writing Prompt #1: Worth a Thousand Words

|

| Aaron Siskind, San Luis Potosi 16, 1961 |

"[t]he Photograph does not call up the past . . . [t]he effect it produces upon me is not to restore what has been abolished (by time, by distance) but to attest that what I see has indeed existed"

— Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida

"People take pictures of the summer / Just in case someone thought they had missed it / Just to prove that it really existed // People take pictures of each other / And the moment to last them forever / Of the time when they mattered to someone"

— the Kinks, "People Take Pictures of Each Other" (view here)

Proverbially, a picture is worth a thousand words, and while I'm not going to ask you to write that many, for your first prompt, I'd like you to respond poetically to photography. Pick one, or maybe two photographs — preferably ones that are one the web, because I want you to include it with your poem — and spend a little time meditating upon them, free from distraction, then start writing down your impressions.

Is there are story being told here? Are there small details that we need to be reminded of? What do you see in this photograph that no one else would see? What does it remind you of? How would you describe the qualities, the textures, the colors of this image? What sort of rhythm does it have? If you choose two photos, what sort of relationship or dialogue might exist between them? Is this a personal picture? If so, what feelings does it stir in you? Why is it important? If it's not a personal photo, then invent a personal connection.

Jot down your initial impressions, then start crafting them into a first draft of your poem. Take a little time away from the photo (maybe a day or so) then come back and see what you have to add or subtract. Post your finished poem along with your image(s) (preferably embedded into the thread) to Blackboard before Friday's class, and we can spend a little time talking about them after the day's workshops.

[ note: you shouldn't write about the photos I've posted here. They're simply intended to give you a few ideas in terms of the sorts of images you might want to choose: a portrait, a scene, an abstract image, etc. ]

|

| Philip-Lorca diCorcia, Hartford, 1980 |

Is there are story being told here? Are there small details that we need to be reminded of? What do you see in this photograph that no one else would see? What does it remind you of? How would you describe the qualities, the textures, the colors of this image? What sort of rhythm does it have? If you choose two photos, what sort of relationship or dialogue might exist between them? Is this a personal picture? If so, what feelings does it stir in you? Why is it important? If it's not a personal photo, then invent a personal connection.

|

| Helen Levitt, New York, NY, 1971 |

Jot down your initial impressions, then start crafting them into a first draft of your poem. Take a little time away from the photo (maybe a day or so) then come back and see what you have to add or subtract. Post your finished poem along with your image(s) (preferably embedded into the thread) to Blackboard before Friday's class, and we can spend a little time talking about them after the day's workshops.

[ note: you shouldn't write about the photos I've posted here. They're simply intended to give you a few ideas in terms of the sorts of images you might want to choose: a portrait, a scene, an abstract image, etc. ]

Wednesday, March 23, 2011

Workshop Format and Responsibilities

Welcome to our poetry workshop! I hope that the next ten weeks will be a productive and exciting time for all of us.

Given my past experience with workshops of all sorts, I've come to realize that the truest value of the time we'll spend together isn't so much the work that we'll do in and of itself — the poems we'll write, the feedback we'll give and receive — but rather the relationships that will begin here and carry on into the future, as well as the habits we'll develop, the objective self-assessment we'll learn to perform, the things we've never tried before that we'll do here because we're forced to. Towards that end, I've tried to structure this workshop so that you'll get the most out of our limited time, but also be well-set to carry on independently after the quarter is over.

In an ideal world, this workshop would be twice as long and half as many students in it. Because that's not the case, we'll try to do our best to ensure that everyone is able to have as many opportunities as possible to receive feedback on their work, and in addition to formal workshop time, there will be plenty of exercises for you to take part in over the course of the term, receiving more informal feedback from me as well as your classmates.

We'll have to run a tight ship in regards to scheduling this term, therefore discussions of student work will be timed and limits will be strictly enforced (though it pains me to do so). If we keep on schedule, we should have enough time for all 20 students to have a poem workshopped for 3 periods of 12 minutes each this quarter — and with this time limit, we'll be sure to have extra time to discuss readings, exercises and our final projects.

It should come as no surprise to you that your final grade will be largely dependent on the quality of the work you produce this term, and here are some of the assignments that will factor into that:

- your response to our initial workshop questionnaire

- the three poems you present during your workshop sessions

- the poems you present in response to our various supplemental writing prompts

- your final portfolio, which will consist of 5-7 poems with revisions and a self-assessment

- the chapbook that you'll create and distribute at the end of the quarter

Because everyone comes to our workshop at different points in his or her writing life, there's no objective standard applied when evaluating student work. Instead, what I'll aim to measure is your openness to the workshop environment — i.e. your willingness to devote serious attention to the assignments, be self-critical and accept constructive criticism, and above all demonstrate a marked development throughout the course of the term. Moreover, your efforts towards your own work aren't the only reason why you're here: to be a good citizen of this workshop, you'll spend almost as much energy addressing the work of your peers as you do your own. Specifically, here are some of the things you'll need to do for your classmates:

- you'll provide a thoughtful and constructive critique of all poems up for workshop on a given day, making use of the comments function in Word (select text, then go under Insert > Add Comment); after you add your first, a comments toolbar will appear) to add marginalia, notes, suggestions, etc. as well as writing up a more substantive response to the poem approximately 150 words in length.

- you'll serve as "lead reviewer" for the workshops of three of your peers' poems — this means that you'll a) write a longer, more detailed critique of the poem being discussed (approximately 250-300 words) and b) start our discussion of that poem by speaking to the poem's strengths and weaknesses for 2-3 minutes.

- you'll show up to class each day prepared to actively take part in our class discussions

Finally, a word about aesthetics: each of us is continually developing our own idiosyncratic poetics, and the diversity of our perspectives should be a strength for our workshop, however, an important part of constructive criticism is making an honest effort to understand the author's intentions and work within that context, and the same goes for form, scale, etc. If your tastes run to the traditional side, but you're responding to the experimental work of a classmate, it's probably not the most helpful advice to casually suggest that she implement strict iambic pentameter; likewise, suggesting a long, rambling addition to a poem working in a minimalist fashion probably won't help much. At the same time, there may be cases where you feel that radical changes are necessary, and if you can explain your convictions behind these beliefs, you may very well be doing your peer a great favor.

You'll be expected to meet all deadlines in regards to the workshop process. Poems should be posted to the appropriate Blackboard threads three (3) days in advance of the workshop, for example:

- poems for Monday's workshop should be posted by the previous Friday evening

- poems for Wednesday's workshop should be posted by the previous Sunday evening

- poems for Friday's workshop should be posted by the previous Tuesday evening

All marked-up workshop copies should be posted by the morning of the workshop, and at the absolute latest (only in cases of extreme circumstances) you should post your comments no later than one week from the workshop date. I'll keep tally of this throughout the term, and multiple latenesses will negatively affect your grade. Finally, poems written in response to one of the prompts should ideally be posted within one week of when the prompt is announced.

Here are a few other important policies:

Attendance and Participation: The importance of both regular attendance and class participation cannot be understated — without both, our workshop will fall apart. In most of the classes I've taught at UC, most students have taken our collaborative work seriously and attendance hasn't been an issue. Ideally, I'd say that you shouldn't miss any classes this term, but I understand that illness, family life and other contingencies are likely to intervene, therefore I think that missing one or two classes (if necessary) is acceptable. However, students who miss more than five classes will automatically fail the course. Think for a second about what this represents: if you miss six classes out of the twenty-six that we'll have after today, you'll have lost almost a quarter of the term.

Communications: We'll use a variety of methods to communicate this term. Because I believe in open pedagogy, we'll be using this blog for the majority of our course announcements and assignments — please use the links above to subscribe via e-mail or RSS, or if you're on Blogger, "follow" this blog so that you'll be kept up to date. I've created a Facebook group for more informal class communications and conversations, which you should join as well (there's a link on the sidebar also). Finally, Blackboard is really dreadful but it does offer a secure and confidential venue for easily posting documents, so we'll be making use of our class forums to share poems, critiques, etc.

Communications (2): Please make use of my posted office hours, the time before and after class, e-mail and/or Facebook to discuss your performance in the workshop, pose questions you might have, etc. If you're having trouble making a contribution, feel that you're doing poorly, or just not getting into the spirit of the course, it's better to ask for guidance sooner rather than later. Unofficially, you should meet with me at least once during the quarter.

Days Off: Class will be canceled on a total of three days throughout the term — on Monday, May 30th for Memorial Day, and on Wednesday and Friday, April 27th and 29th, when I have to be out of town, first for a panel talk at UPenn (on Tuesday afternoon), followed by the Post45 Conference in Cleveland (at 8:00 Friday morning). I think if our workshops are running on schedule, this shouldn't be an issue and everyone will be able to get their full number of presentations in, however if necessary, I'll try to schedule a make-up date.

Final Meeting: There will not be a final examination for this class, but we will meet during the scheduled final exam period, at which time your final portfolios, self-appraisal and chapbooks will be due. We'll take advantage of the time for everyone to be able to discuss the process of making their chapbooks, as well as the general lessons you've taken from the workshop experience. Attendance at this meeting is mandatory (as any other final exam would be) so please make travel plans accordingly.

Technology: In theory, technology is a wonderful thing, but in the classroom, it can be a distraction. Please make sure that your cell phone is turned off (or at the very least in silent mode) before class begins, and keep it in your bag throughout. Texting during class will not be tolerated. Laptops may only be used by students with appropriate paperwork from Disability Services explaining its necessity—otherwise, a notebook or binder will have to suffice (even if it's terribly old-world).

Special Needs Statement: If you have any special needs related to your participation and performance in this course, please speak to me as soon as possible. In consultation with Disability Services, we can make reasonable provisions to ensure your ability to succeed in this class and meet its goals.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)